Monarch Butterflies

RANGE

Monarch butterflies are nativeto North and South America, but they´ve spread to other warm places where milkweed grows. No longer found in South America, monarchs in North America are divided into two main groups: The western monarchs, which breed west of the Rocky Mountains and overwinter in southern California; and the eastern monarchs, which breed in the Great Plains and Canada, and overwinter in Central Mexico. There are also populations in Hawaii; Portugal and Spain; and Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere in Oceania.

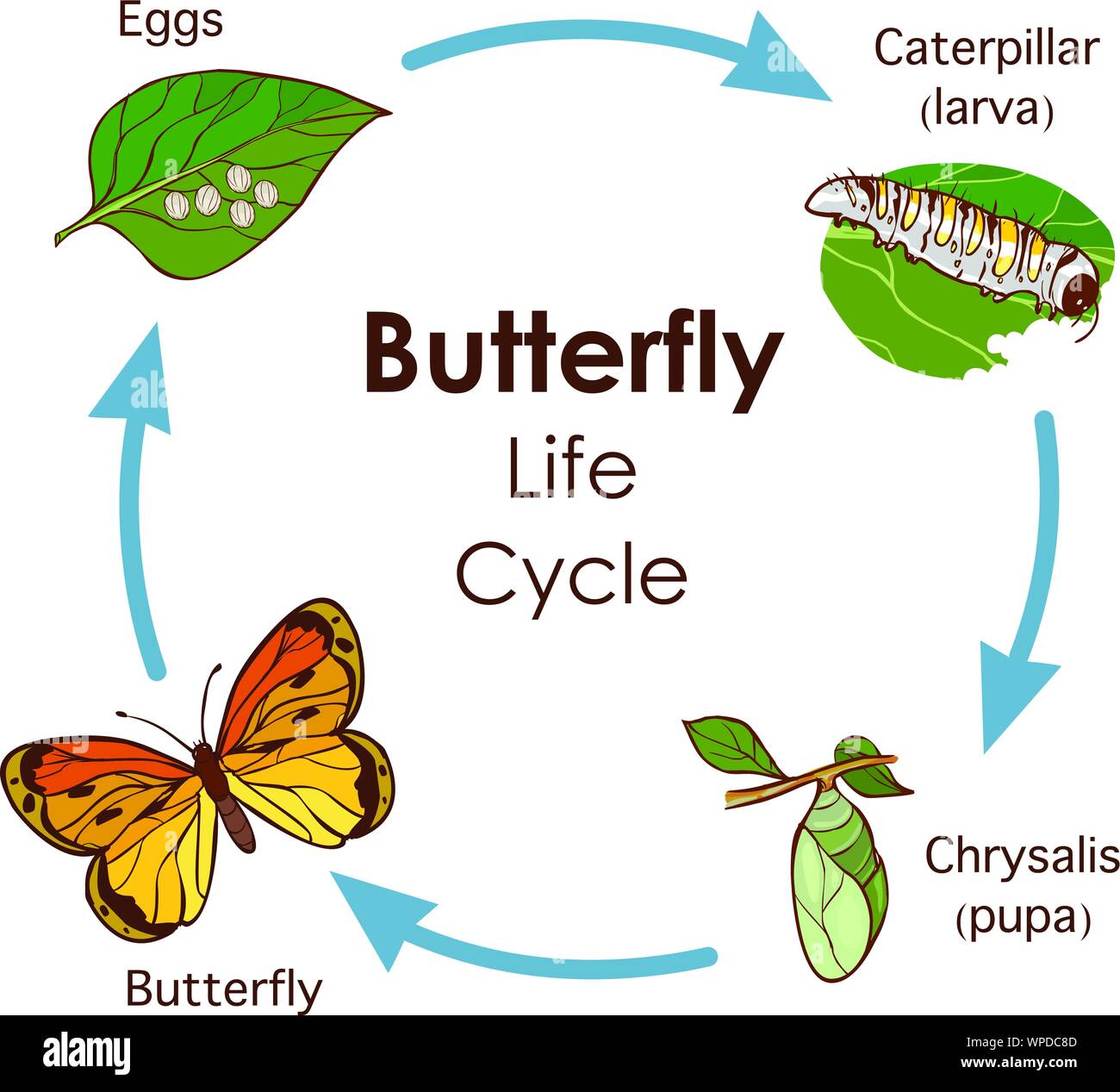

The female monarch butterfly lays each of her eggs individually on the leaf of a milkweed plant, attaching it with a bit of glue she secretes. A female usually lays between 300 and 500 eggs over a two- to five-week period.

After a few days, the eggs hatch into larvae, otherwise known as caterpillars in the moth and butterfly world. The caterpillars’ main job is to grow, so they spend most of their time eating. They only eat milkweed, which is why the female laid her eggs on milkweed leaves in the first place.

The caterpillars eat their fill for about two weeks, and then they spin protective cases around themselves to enter the pupa stage, which is also called "chrysalis." About a week or two later, they finish their metamorphosis and emerge as fully formed, black-and-orange, adult monarch butterflies.

Monarch butterflies do different things depending on when they complete their metamorphosis. If they emerge in the spring or early summer, they’ll start reproducing within days. But if they’re born in the later summer or fall, they know winter is coming—time to head south for warmer weather.

Defense

Monarchs’ colorful pattern makes them easy to identify—and that's the idea. The distinctive colors warn predators that they’re foul-tasting and poisonous. The poison comes from their diet. Milkweed itself is toxic, but monarchs have evolved not only to tolerate it, but to use it to their advantage by storing the toxins in their bodies and making themselves poisonous to predators, such as birds.

Migration

In the east, only monarchs that emerge in late summer or early fall make the annual migration south for the winter. As the days get shorter and the weather cooler, they know it’s time to abandon their breeding grounds in the northern U.S. and Canada and head south to the mountains of central Mexico, where it’s warmer. Some migrate up to 3,000 miles.

There, they huddle together on oyamel fir trees to wait out the winter. Once the days start growing longer again, they begin to move back north, stopping somewhere along the route to lay eggs. Then the new generation continues farther north and stops to lay eggs. The process may repeat over four or five generations before the monarchs have reached Canada again.

Western monarchs head to the California coast for the winter, stopping at one of several hundred known spots along the coast to wait out the cold. When spring comes, they disperse across California and other western states.

How do monarchs make such a long journey? They use the sun to stay on course, but they also have a magnetic compass to help them navigate on cloudy days. A special gene for highly efficient muscles gives them an advantage for long-distance flight.

the boterflys haf a cicle live

ReplyDelete